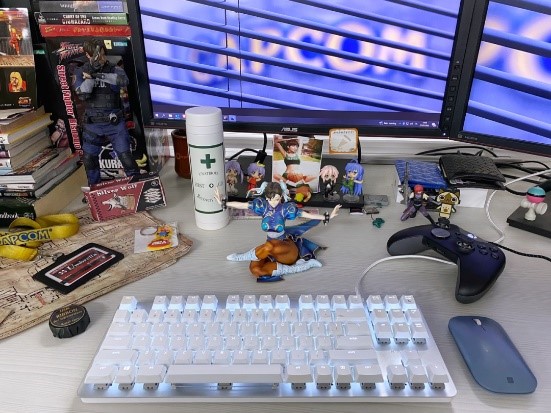

Many know Capcom as the game developer who created the likes of Street Fighter, Monster Hunter, Resident Evil, and more. Behind the company name is a team of talented and dedicated individuals who work together to develop your favorite games through a herculean effort. We thought we could pull back the curtain a bit and introduce you to these members of the development team who have a direct hand in making our games. First up is the Localization Team from Capcom’s HQ in Japan!

- To start off, please tell everyone about yourself

Andrew: My name is Andrew and I’m originally from Toronto, Canada. I moved to Japan almost two decades ago. I’ve been at Capcom for 15 years and I’m a Localization Director plus the localization group manager for English localization. I started as an English teacher in Tokyo, but I was lucky enough to be picked up as an English editor by Capcom. I’ve been working on the Monster Hunter series since Monster Hunter Freedom up until Iceborne, and I’ve also worked on Ace Attorney, Mega Man, Devil May Cry, and Street Fighter.

Stefano: Hello everyone, I’m Stefano. I was born in Naples, Italy and I’ve been with Capcom for almost a decade. I work at the Osaka HQ in Japan, mainly as an Italian Localization Expert, and I also develop internal tools and web applications.

Alberto: Hi! My name is Alberto. I’m from Spain and I’ve been a Spanish translator/editor at Capcom for 10 years now. As someone who grew up with games, got a translation degree, and loved Japan to the point of moving here, finding this job was like making it to the Holy Land. I feel very fortunate that my work is part of some of the franchises I’ve always loved most.

2. Walk us through a typical day for the localization team

Stefano: A good day always starts with a hot coffee, hopefully from fresh (hand-ground!) coffee beans. And a sweet breakfast…I’m Italian after all. This is also a good time to check gaming related news and see what’s happening in the rest of the world.

As you can imagine, day by day activities can vary greatly depending on the tasks at hand. Some days I’ll be working on game text, localizing tons of words to meet deadlines, while other days I can fully focus on the games themselves, getting to play them as they are being developed, and making sure our text is always contextually accurate.

We are free to organize the workday as we wish, and I can always find time to work on other projects such as developing or maintaining internal tools and web apps, and generally assisting other team members with problems that require some technical knowledge.

It’s not a solitary job either. While sometimes I can focus on my work by myself, oftentimes I work together with other teammates to solve issues, figure out the answers to some questions we might have, or work closely with my other language partner Veronica, assisting her with her projects. And of course, there can be a lot of meetings too!

Alberto: You usually have to self-manage your time to translate new text, edit text strings to reflect changes in the source, check the in-game accuracy of text strings, report issues found in games and follow their progression, discuss any of these issues with your colleagues in charge of other languages, etc. We have a lot of other tasks too related to voice recording, being consulted for certain design points, and promotional websites and materials, to name a few. The tasks above are what keeps me busy most of the time – and don’t forget, I’m juggling all of this for multiple projects at the same time!

Andrew: I’m a little bit different than Stefano and Alberto because while they’re working primarily with in-game assets, I work with schedules and have a ton of meetings every day. There’s a lot of set up involved in localization to delivering the highest quality possible, so I usually find myself translating or writing reference guides instead of working on the translation itself or I’m joining meetings to figure out our milestones and other project needs that senior team members have to worry about!

3. What’s an important aspect of localization that most fans don’t realize?

Stefano: Localization can be very chaotic and it’s very different from working on an already finished product, such as a book or a movie. Also, players don’t always realize how much text there can be in a game (typically a lot more than someone would expect). Therefore, it can be very challenging to ensure everything is accurate with the least number of mistakes possible.

The translation itself can be influenced by many factors, including character limits in the interface (we often work closely with members of the User Interface or UI team to ensure those are suitable for all languages), the use of textures, the font choice, and other technical related limitations.

Alberto: With a developer/publisher like Capcom, the hardest challenges come from working simultaneously with a game under development. Adjusting to time constraints, having to respect legacy terminology while finding issues in it, translating for parts of the game you don’t fully understand yet, and working on an ever-changing source text while keeping overall consistency is not easy. It is important to realize that when you’re looking at a finished product, a game you love and have put many hours into, and has reached a point that it is not going to change and is self-contained; you can judge its localization from a vantage point that is not akin to what the actual job is like.

Also, some aspects of the game (like dialogue, or voiced lines) attract a lot of attention, but the bulk of the job often comes from UI text, menus, system messages, etc. that amount to a lot more volume than people realize and need lots of work for contextual accuracy and consistency. Doing a good job with all those strings simply means your work will go completely unnoticed.

Andrew: Forecasting what we need to do months and months ahead of time is probably the biggest challenge for the localization team. The localization directors usually join the team at the pre-production stage, but the real bulk of the work doesn’t start until midway through the project. A good localization team needs to be attentive and catch early warning signs to avoid major issues. A simple example would be when the team is designing their menus and they fit just fine for Japanese text but are way too small for any other language. We try to catch those issues early and ask them to adjust the size of menus so we can translate as accurately as possible.

4. Given that the localization team works on almost all of Capcom’s major titles, what’s the difference between localizing a fighting game, a Monster Hunter game, and a Resident Evil game?

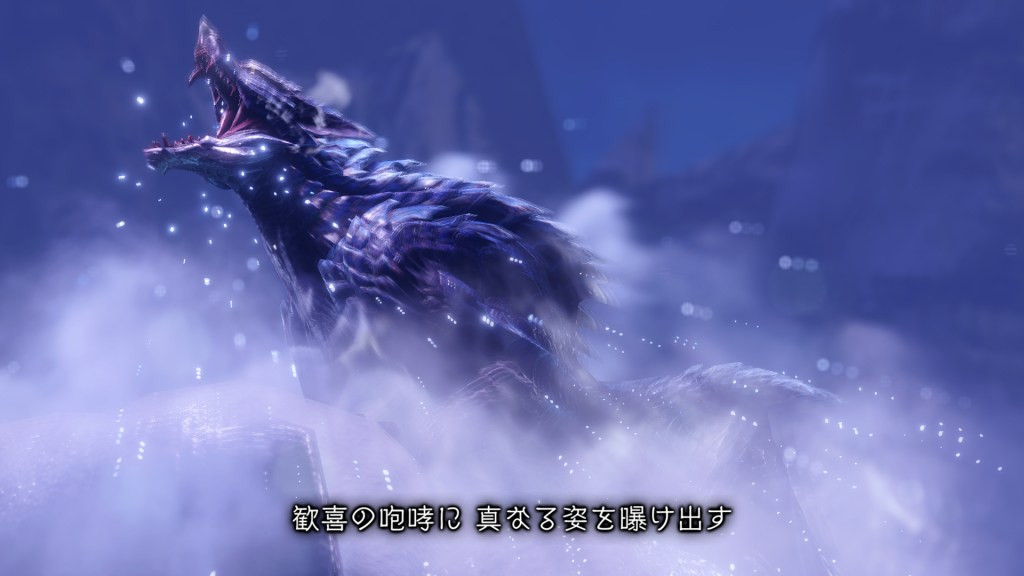

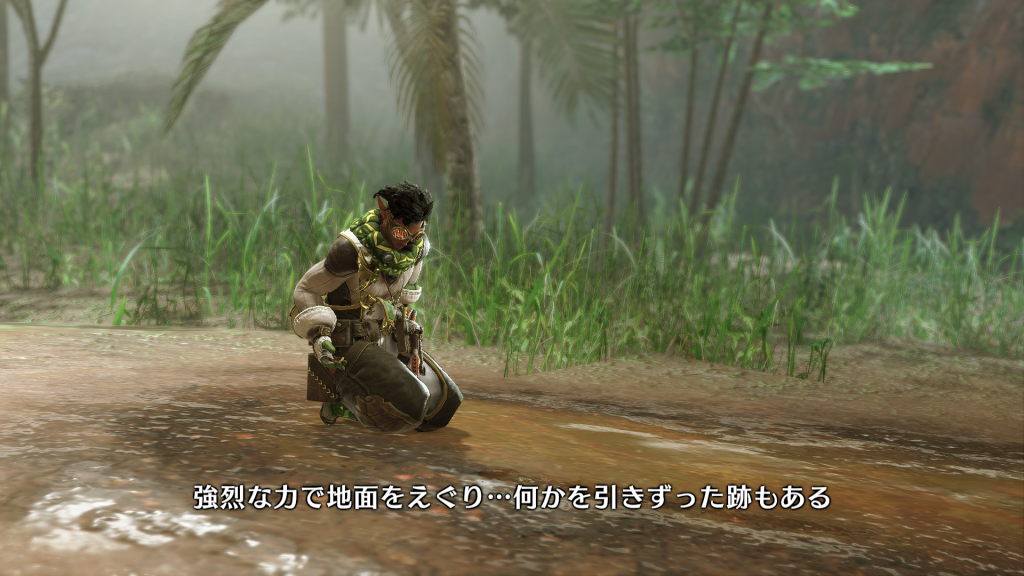

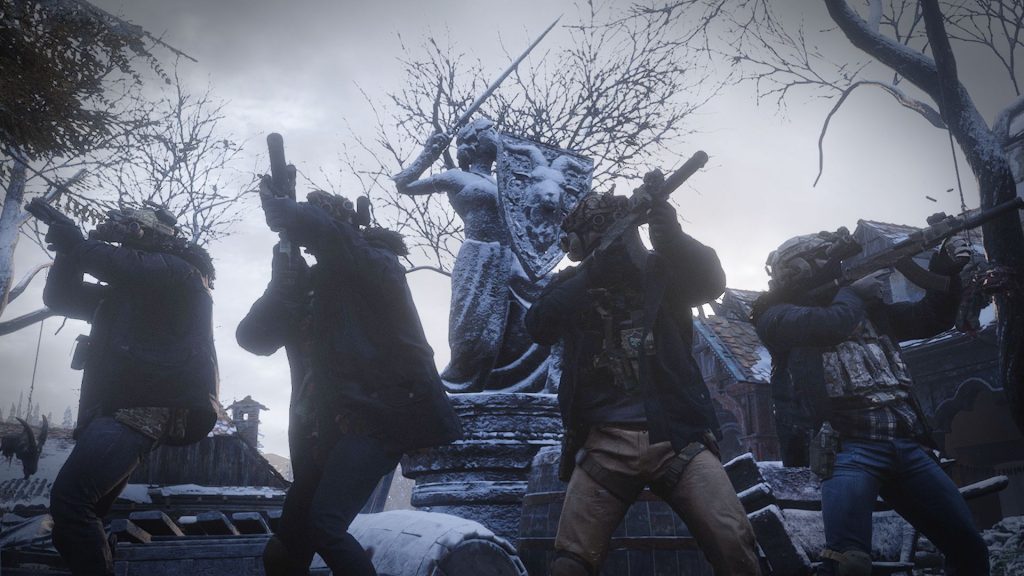

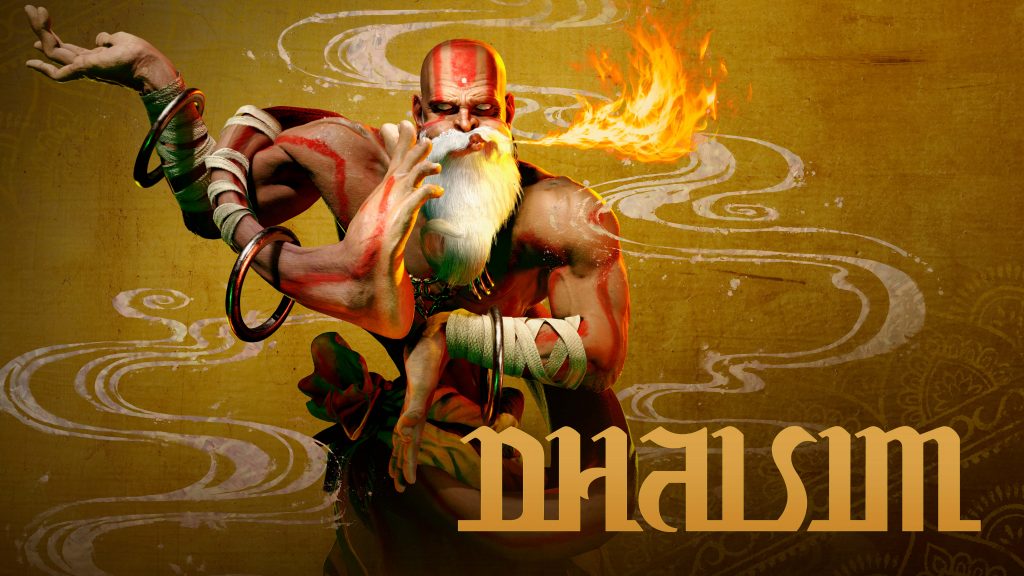

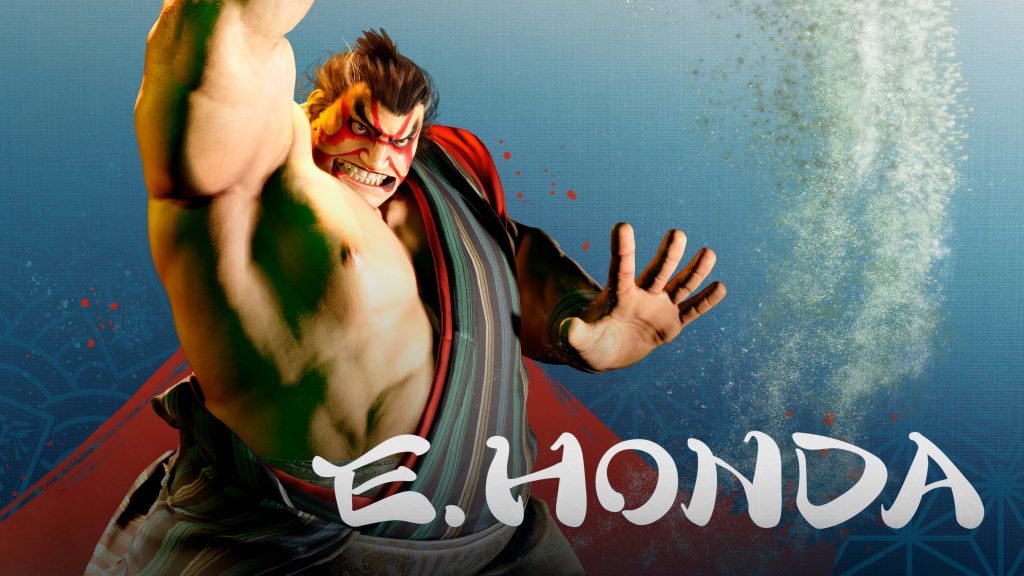

Stefano: While general localization principles apply to almost everything, each title comes with its own internal style and tone. Monster Hunter games have all kinds of varied characters with funny dialogue, while a Resident Evil game might require a slightly more scientific and military style tone for its in-game files. Finally, Street Fighter has a good mix of creative dialogue along with very specific and sometimes obscure fighting game lingo, which could be challenging if one is not very familiar with the genre. Having a broad knowledge of all Capcom titles is helpful, but each one of us has developed, with time, a certain specialization for a specific series. Teamwork is essential in this case, and we always try to help each other out. Thankfully, we have built a lot of resources over the years and as mentioned above, there are many knowledgeable people in our team that can always lend a hand.

Alberto: They have different tones overall that obviously make their localization very different. My approach to an RE game is that it should sound very much like a movie. Monster Hunter is a lot more lighthearted, but a fantasy world setting has a lot less obvious constraints – you can’t use expressions or references that may sound too modern or relate to elements of the real world that may momentarily break a player’s immersion or may not even exist in the universe of the game. Street Fighter on the other hand is more modern sounding – and even more so in SF6, with its youthful, street-culture vibe. The Spanish fighting game community uses a lot of terms in English, and in SF6 we’re reflecting that in the game rather than trying to fight it.

Andrew: To add to what Stefano and Alberto touched upon, with Monster Hunter you really want to be on the ball with your word choice and keeping it consistent. Great Sword is always going to mean the weapon type that hunters use and nothing else, so translators must avoid using it in a different context to minimize confusion. Street Fighter, on the other hand, takes a lot from its community and we try to use terms that the fans have coined themselves because we feel it’s an organic evolution, and it makes communication within the community better and more genuine. We have no issues using “super meter” in the translation, even though the official term is Super Art Gauge, because that’s what the community is comfortable using. You’ll see this a lot in Street Fighter 6’s new commentary feature!

5. What was your favorite moment or line to localize?

Stefano: It’s happening right now! I’m working on Street Fighter 6 and not only it is fun to adapt some iconic characters like Ryu and Chun-Li in Italian, but also coming up with accurate and relatable player titles and other in-game text for the Italian fighting game community can be a very rewarding experience.

Alberto: I generally like humorous characters and dialogue best. Jokes are hard to localize, but it’s fun to think of different alternatives to keep the core information part of the message, the laughs, and other nuances ─ it’s a welcome challenge.

On the other side of the spectrum, pre-Capcom I once translated a game based on Greek mythology where literally every line of dialogue was very solemn, heavy, and epic sounding. That was quite challenging and satisfying in its own way too.

Andrew: I loved localizing the Fatalis and Alatreon updates in Iceborne, and pretty much all of Street Fighter 6 has been a real blast to work on. Thanks to our dev schedule, I was able to dedicate a lot of time to the commentary script, and I think I came up with a ton of great lines for all of our commentators to work with.

6. Do you have a favorite character to translate?

Stefano: Can Resident Evil files be considered characters? Generally, many characters in the series speak through those, and most of the lore can be hidden in there. I always liked to explore and collect those files in the old games and now it’s always a pleasure to be able to work on those.

Alberto: In the vein I mentioned above, I quite liked translating the dialogues of the Melder Lady in Seliana (MH Iceborne). In English, she tries to mimic youth slang and always gets it wrong, so in translating these lines I thought her age would be even more emphasized by her confidently using hilariously outdated slang from the 70s and 80s. Those lines were fun to write and I’ve heard good feedback from players who liked them.

The Hell Hunters are very fun to translate too. I love these types of characters that are so full of themselves, high on pride, and full of empty threats, yet keep sounding a bit ridiculous overall.

Andrew: I had a lot of fun translating Luke, Jamie, and Kimberly in Street Fighter 6. From Monster Hunter, I enjoyed translating the Ace Commander from Monster Hunter 4 Ultimate and the General from Iceborne’s Fatalis update.

7. How closely do you work with the development team?

Stefano: The localization department is part of development and while we may not always sit close to each other, we try to collaborate with the team very early on. With the help of Andrew, we try to solve many potential issues, not only on the technical side (textures, UI) but also cultural (characters, their origin stories, or the content of stages). The team is always very responsive when changes are needed due to cultural differences, to ensure that the final game can be enjoyed and understood by everybody around the world.

Andrew: Localization Directors like me join the team in a project’s early stages, so we move our workstations to where the team is located and stay there until the project is over. Since we’re part of the team we have daily contact with the directors, game designers, writers, producers, etc.

This also means that we’re talking with everyone on the team to figure out story beats, schedules, recording sessions, UI adjustments, etc. It’s an intensive job because we work with the dev team to figure out everything, then we also manage our costs and milestones with our localization coordinators.

8. There’s a shift in tone in Luke’s character coming from SFV to SF6, could you describe how you handled that in localization?

Alberto: I think his change in tone matches that of the game – more youthful, modern, and with a higher presence of street culture. As a new character to SFV, what we knew about him mostly focused on his origin story, but there was a certain mismatch between the gravity of that story and his general image. This time the focus is not on his past. He acts as someone who introduces us to the game, and so his tone is a cornerstone of how we perceive SF6. He’s a master, but with no wise old man tropes. I think of him as a bit of a young but confident, “cool gym bro” type.

Andrew: There’s a definite personality shift. Luke’s still the same person but we’ve worked very closely with the scenario writer on the project and taken efforts to make sure players understand why this change happened. We think that once players get their hands on the game, they’ll understand a bit about what happened with Luke.

9. Finally, do you have any advice for people who are interested in working in localization?

Stefano: Play a lot of games (and consume other media) in your native language, that helps for sure. Never forget to have fun and enjoy the games you might help make one day.

Alberto: First off, in my opinion, the localization path may be one of the more challenging ways to “get your foot in the door” of the video game industry – this may result in adverse effects to the quality of the work produced and your career options alike. Localization is its own specialized thing and may not lead to opportunities in game design, programming, etc.

If you’re interested in localization though, go for it! You’ll need strong writing skills and as much fluency in a foreign language – as a translator/editor, your most needed skill is producing good quality text in your own language. Ideally, follow some formal training to learn how to translate. Once you’re ready, working as a localization tester can open the door to better localization positions later.

Andrew: Strong writing skills in your native language is an absolute must. Being able to write in a variety of styles is also ideal, especially if you’re working in a company like Capcom where you’ll often jump from say, Monster Hunter to Resident Evil to Street Fighter. Other than that, good communication and organizational skills are very important and help separate the good localizers from the great ones.

Also, as one of the group managers in localization I have to mention that we’re actively looking for localizers to join our team in Osaka, Japan! We’re actively looking for a localization director, but if you want to join our team as a localizer for a language that we support full time (French, Italian, German, Spanish, Korean, Simplified & Traditional Chinese, Brazil-Portuguese, Polish, Russian, Arabic), don’t hesitate to send in your CV!

(Capcom careers page: https://job.axol.jp/bw/c/capcom/job/list)

And that’s the end of the interview! Hope you enjoyed getting more insight and a behind the scenes look into how localization works at Capcom. If you want to see more, please let us know through our official Capcom Twitter @CapcomUSA_!