The Zen of Dead Rising

Sep 06, 2014 // GregaMan

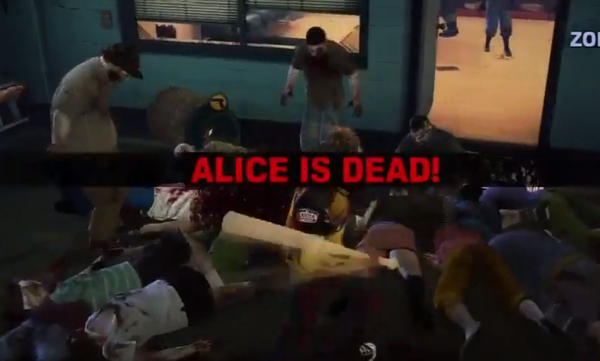

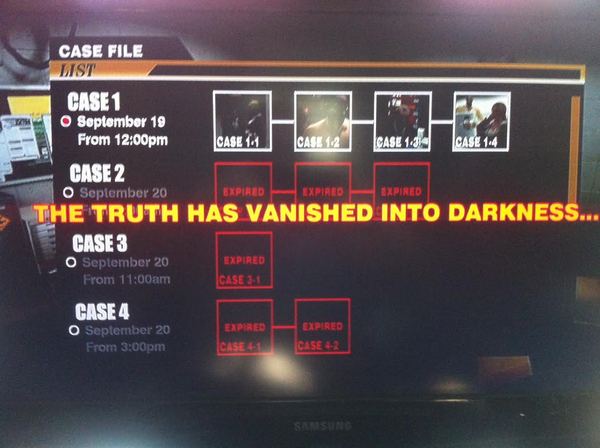

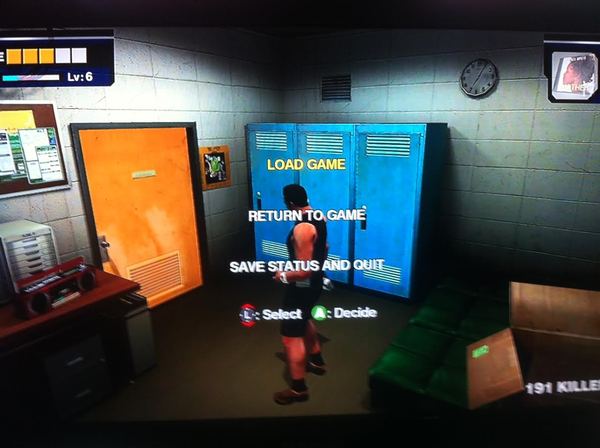

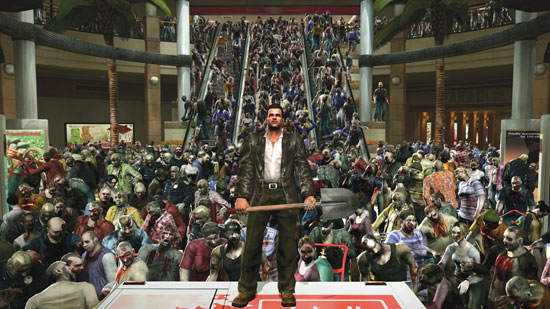

When the original Dead Rising came out in 2006, I think it blew a lot of minds. Somehow, it managed to simultaneously offer Xbox 360 owners the most liberating and the most restrictive sandbox game of all time—a game where the player was free to roam around and do pretty much anything he or she wanted, but where he or she must also adhere to a strict time limit and trudge through constant antagonism at an oppressive level of difficulty to see the main storyline through. A sort of quicksandbox, if you will. The real-life story that initially emerged amongst hapless Dead Rising players, as I recall it, was frequently one of confusion, or worse still, disappointment as it dawned on them that the “game” present within the game was not as simple as bludgeoning shambling meat bags with your weapon of choice and playing dress-up to your heart’s delight. But to be sure, the game blew minds. It had both a technical heft and a refreshing subversiveness about it that seemed to ring in a new generation of gaming. It was a promise that we gamerkind still had new ground to tread, new magic moments to discover; and that alone was enough to secure both a mainstream and a cult following—not a common feat in any medium. So what is Dead Rising, at its heart? Like any other zombies-in-a-mall piece you can name, DR seems to have a bone to pick with consumerism, or at least an elbow to nudge. Our guest David noted in the latest podcastthat one original source of inspiration for the series came when its Japanese creators observed the casual wastefulness of an American colleague at a fast food restaurant. But let’s face it: whatever social commentary Dead Rising might have presented on the matter of consumerism was at least a little muffled by the game’s very place within the medium—a bullet-pointed and shrink-wrapped retail product whose console exclusivity was touted to help sell new machines. And quite smartly, I might add! I know I’m not the only one who drooled over those first gameplay videos and screenshots, and there’s a good reason all three of the numbered installments have broken a million sold, even on new hardware. Or is that just part of the commentary? But no, there’s something much more thought-provoking and unique about Dead Rising than the anti-consumerism angle , something about how the series works and how it taps into the unique characteristics of the gaming medium. It has to do with freedom, choice, and how we cope with crises. You see, Dead Rising, at its heart, is a meditation on life, death, and truth. Like Monster Hunter and Street Fighter before it, Dead Rising is as much a sort of simulation as it is a game. Where Monster Hunter and Street Fighter offered near one-to-one representations of the experiences of being a monster hunter and taking part in a martial arts tournament respectively, Dead Rising offers players not simply a game where you kill zombies, but rather an open-ended zombie apocalypse scenario where, because it’s a zombie apocalypse scenario, you incidentally canand are likely to kill zombies. At no point are you required to kill zombies—in fact, you’re not really required to do anything. ↑ At times, it’s an awful lot like Street Fighter. Every Dead Rising game takes place in an open world occupied by a lurching, undulating sea of the undead, casting you, the player, as an “everyman”—a character who symbolizes (certain aspects of?) the average real-life man (and I suppose attempts to at least stand in for the average real-life woman). Every game also offers a linear, narrative-driven campaign. But weirdly, and crucially to my point, this campaign is presented as just one possible outcome that may occur given the aforementioned scenario, and never does the game presume that this is the outcome that your actions will dictate. As a matter of fact, I’d say Dead Rising gives you somewhere between seven and forty very good excuses to just abandon your mission altogether and go try on sundresses. For one thing, each game starts off with the player witnessing, in real time, the unavoidable death of several NPCs. These NPCs look just like the other rescuable “Survivors” you’ll encounter throughout the series, but their deaths are unpreventable. If the first enemies encountered in Inafune’s Mega Man X are there to instruct the player how to play the game, then these first “Survivors” in Dead Rising are likewise there to teach you the rules of Dead Rising.All control henceforth is an illusion, the game says. The zombie apocalypse is to be accepted as a pretense. The world cannot be saved. Few players really let that sink in when they get to that moment in each game, but the longer the Dead Rising series goes on, the more apparent the message becomes. The DR timeline now spans more than fifteen years, and the world is still in zombie hell. What did you think you were accomplishing? But hey, the game says. Do anything you like. It is in this way that the game gives the player free will, but nothing to do with it. The real challenge posed by Dead Rising, I would argue, is for the player to ascribe his or her own value to his or her own actions, accepting that there is no value to any action other than that which he or she ascribes. Here’s what I mean: The “main” storyline of each Dead Rising game is locked to an ever-ticking timeline. This is one way that the game differs from other open world games.In most open-world games, the story missions are ever-present beacons on a map; they’ll wait two, four, or five-hundred hours while you goof off at the bowling alley or go on an epic killing spree. When you’re ready, you can go to a mission beacon and pick up the story wherever you left it. I left some poor guy waiting in San Andreas nine years ago and he’s still there. In Dead Rising, the story doesn’t care if you pick it up or not. If you show up late and miss it, you’ve just missed one possible outcome of the average-dude-in-zombie-hell scenario. Missing it, however, is itself another possible outcome of equal weight and import. The game affirms that notion itself, and here’s how: When you let the time run out on the “main” campaign, a piece of text appears on screen: “THE TRUTH HAS VANISHED INTO DARKNESS…” The game then gives you three options: There are a number of implications here. One is that the objective ostensibly posed by Dead Rising to the player is to seek out “THE TRUTH.” This is the “game,” in case anyone from Walmart asks. Another is that the player’s decision to reject that objective is utterly valid—Dead Rising goes on anyway. And it does so after explicitly posing the choice to you. A third is that it is expected, or at least possible, that the player will have to go through multiple incarnations, live multiple lives, before awakening to “THE TRUTH,” should he or she choose to seek it. How very Zen. To begin, I want to emphasize the second of the above implications, because I think it touches on something very rare in video games and special about Dead Rising. The indie game The Stanley Parable cleverly uses the medium of gaming to explore the limitations of meaningful choice in games. So many games, even triple-A ones—especially triple-A ones—offer players a vivid sense of immersion, an illusion of control, but quickly begin to show their seams as soon as a player dares to tread off the beaten path. NPCs will robotically repeat the same line of dialog until the player makes the scripted “correct” choice. Suicidal players will be safely blocked in by invisible walls or else regurgitated to the nearest safe zone after attempting to jump to their demise. No, no, no, the game seems to say. Do it RIGHT. That’s not a bad thing, mind you—but it is comparable to a roller coaster ride. Try as the player might to make independent choices, to have a unique impact on the surrounding world, ultimately it is the preexisting track that determines the player’s course. This is not not the case in Dead Rising, whose endings are all scripted branches, but unlike other games, Dead Rising openly acknowledges the inevitability of the world around you, and this gives weight to your choices in a way that few games do. If you choose to goof off in Uranus Zone for twelve hours, that’s twelve hours you won’t get back. During those twelve hours, people die. Opportunities vanish. THE TRUTH slips through your fingers. But you’re free to do it. A lesser game would let you goof off and see each of those opportunities through afterward, as though the goofing off never even happened. Your choices would be weightless, timeless. ↑ You chose this path. It’s incredibly special and humble, then, that Dead Rising, after presenting you with its own definition of “THE TRUTH” (that is, whatever information lies at the end of the story campaign), fully accommodates the possibility that the player might have a completely different notion of truth, or simply lack interest in pursuing it whatever. More than 1000 years before Dead Rising, a Zen poem called Xinxin Ming (Shinjinmei in Japanese) contained the following advice: “Do not seek the truth; only cease to cherish opinions.” The idea is that the truth is not seekable, but that it is already in front of you, obscured only by your subjective perceptions and presuppositions. It has been likened to a dog chasing its own tail. The dog already has its tail. Similarly, you already have the truth. You are living it. Do you even care? Why are you even playing Dead Rising? Related is the following quote from Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, one of the most widely influential literary works of the last thirty years: “The truth knocks on the door and you say, ‘Go away, I’m looking for the truth,’ and so it goes away. Puzzling.” What if by pursuing the so-called TRUTH dangled in front of you by the game, you’re really just distancing yourself further from the TRUE truth? Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance also deeply explores the concept of “Quality” as a main theme, asking the infinitely deep question, “How does one distinguish ‘good’ from ‘bad’?” Dead Rising games each have multiple endings, popularly described as “good” and “bad” endings. But how are players determining which are which? No ending is truly an “ending,” and no ending is particularly “happy,” given that zombie hell perpetuates to this very day with the release of Dead Rising 3 (“Apocalypse Edition,” no less!). But then again, insofar as video games are something we play for enjoyment, one could argue that the infinite perpetuation of Dead Rising is the happy ending. And to this point, in the first Dead Rising, achieving what is widely believed the “best” ending gives players a bulk of “PP” (Prestige Points, to be discussed later), as well as access to “Infinity Mode” as their ultimate reward. What is “Infinity Mode”? It’s a mode that challenges the player to stay alive as long as possible in zombie hell. In a word—it’s infinite Dead Rising. This is your ultimate reward for seeking THE TRUTH. But weirdly, this, like the dog’s tail, is already something to which you have access simply by purchasing the game. ↑ Con…gratulations? So in effect, the only real qualitative or quantitative difference between seeking THE TRUTH versus trying on dresses for seventy-two hours is the amount of “PP” you receive afterwards. But let’s take a look at PP. The word prestige is synonymous with respect or admiration, generally based on one’s deeds or achievements. In Dead Rising, there are a number of ways that you can earn prestige. One, as mentioned above, is by playing through the main story campaign to obtain a hefty PP reward. Others include killing zombies, taking photographs, or just experimenting with your environment and discovering things (running on a treadmill, for example). There are an infinite number of zombies in Dead Rising, as well as an infinite number of photographs to take. What’s more, neither the player nor Frank West can really share the photographs taken with anybody else since the game predates social sharing features and Frank West is stranded in zombie hell without an internet connection. This suggests that even fruitless endeavors are prestigious deeds simply because the player chose to do them. While seeking THE TRUTH will award you with a large amount of prestige, the player can also choose to gain just as much, or even more, simply by goofing off and taking photographs purely for his own private gratification at the mall. Goofing off in zombie hell is just as much of an achievement as escaping it. ↑ This selfie is purely for Frank’s gratification. #soalone Meanwhile, what does prestige even do? In the game’s terms, PP will increase your “level.” Increasing your level makes you stronger, faster, healthier, and a more capable fighter. It also carries over from one “life” to another (remember, this is a game where you are expected to live multiple lives before uncovering THE TRUTH). In this way, it is not unlike the concept of karma —the notion that your deeds in one life influence the nature and quality of future lives, ultimately leading you to a state of enlightened bliss. But while the acquisition of prestige in Dead Rising can aid you in your path to seek THE TRUTH by making you stronger and faster, ultimately even that path just leads to you acquiring more prestige, suggesting that even by the game’s terms, seeing through the “best” ending is beside the point. And here’s where it gets really mind-bending: in Dead Rising, your level caps at fifty. This is the strongest, fastest, and healthiest you can be. In the first game, your ultimate reward for earning maximum prestige—that is, the culmination of all your accumulated deeds (karma) spanning multiple lifetimes—is a skill called the “Zombie Walk.” The skill allows Frank West to become as a zombie, mimicking the undead around him to blend peacefully into their midst. ↑ The Zombie Walk. I think this bears a moment’s meditation. The highest level of existence in Dead Rising, the most prestigious skill one can acquire, the only way to break the vicious cycle of apocalyptic zombie hell, is to wittingly become a zombie. Only then is peace achieved. …. Here I bring you a quote from The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation by the late Tibetan meditation master Chögyam Trungpa. “There is a story of a king in India whose court soothsayers told him that within seven days there would be a rain whose water would produce madness. The king collected and stored enormous amounts of fresh water, so that when the rain of madness fell, all of his subjects went mad except himself. But after a while he realized that he could not communicate with his subjects because they took the mad world to be real and could smoothly function in the world created by their mutual madness. So finally the king decided to abandon his supply of fresh water and drink the water of madness. It is a rather disappointing way of expressing the realization of enlightenment, but it is a very powerful statement.” Plug in Frank West, Zombrex, and a crapload of zombies, and I think the above passage pretty much speaks for itself. Granted Chuck Greene and Nick Ramos didn’t get the Zombie Walk, but if you told me Chuck and Nick aren’t yet as enlightened as Frank, I’d buy it. The one last aspect of the series I wanted to touch upon is the role of humor. There’s a prominent “zaniness” to Dead Rising that I think people tend to just accept as part of its video gameyness. You can dress up in a wetsuit and Servbot helmet while staring tragedy in the face, and I think there’s generally an understanding on the player’s part that that’s not what’s “really” happening—you’re just messing with the game. But is it so implausible that someone would respond to tragedy or crisis with humor? Be it escapism, therapy, or a genuine shift in outlook, humor has carried people through some terrible times, man, and it’s done so for millennia. In some schools of Zen Buddhism, the spontaneity of laughter is viewed as analogous to that of enlightenment, and absurdist humor is used as a way of jarring an individual out of conventional thought processes restricted by labels, in an effort to grasp reality as it is—that is, the truth. Laughter is thus an expression of enlightenment. And don’t you feel a little bit enlightened when you arrive at a scene of tragedy in Dead Rising dressed like a country gal and armed with a leaf blower? I know I do. Thirty years ago, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance set out to present two-thousand years worth of complex philosophical ideas in a straightforward context digestible to the common reader. Don’t quote me on it, but I can’t help but wonder if Dead Rising isn’t secretly doing the same thing for gamers. And before you tell me that’s far-fetched, I might just gently remind you that, along with making each subsequent game in the series gradually more digestible to the common gamer while preserving the original work’s fundamental ideas (think Off the Record’s Sandbox Mode or Dead Rising 3’s more lenient time constraints), the creators also saw fit to make their second protagonist a professional motorcyclist and their third protagonist an auto mechanic. So yeah. —————– I’ll be honest: I didn’t expect this blog to write itself as much as it did after my initial idea. But it did. So I take that as evidence that there might actually be some legitimate points here. But I’m dying to know what other people’s thoughts are on the subject. I hope it paints the series in a new light that is exciting for both newcomers and long-time series fans. I, for one, am now going to go play some DR. Thanks for reading!

-

Brands:Tags:

-

Loading...

Platforms: